- Scroll for more information

Begin Your Journey

State court civil justice systems are increasingly challenged by inefficient, burdensome, and difficult-to-navigate court filing processes. Needlessly complex court forms and outdated filing systems not only impact attorneys and court personnel; they also increase costs and make our state courts inaccessible to the growing number of self-represented litigants. Using the Filing Fairness Toolkit, courts and court partners can take concrete steps to address these challenges by modernizing their forms and filing systems, which will improve the experiences of all court users.

- The Filing Fairness Toolkit is an effort by Stanford’s Filing Fairness Project to tap wide-ranging research and expertise to offer concrete recommendations about court modernization in a single place.

A research team drawn from law, computer science, and business has spent nearly 2 years talking with key stakeholders, including state supreme court justices, court technologists, and access to justice experts to understand these challenges and ways to address them. This Toolkit distills learning from our research and conversations into actionable recommendations. Fortunately, each of the recommendations presented is already in use, for minimal cost, by various courts in the United States.

Get Involved

Key Takeaways

01

Modern court filing systems and processes reduce administrative burdens and costs for courts and clerks, improve judicial efficiency, and increase access to justice by making it easier for all court users to find, prepare, and submit the information courts need.

02

Increasing access to justice through modern court filing is easier and takes fewer resources when courts collaborate to scale solutions using readily-available technology that is already implemented in other courts and sectors.

03

Courts can optimize the benefits of filing system modernization for court staff and users by:

- Adopting standards and facilitating connections between filing system components

- Developing creative public-private partnerships

- Implementing procurement practices that promote flexibility and innovation

- Standardizing, simplifying, and automating court forms

- Reducing procedural barriers to efiling

04

Judges, administrators, clerks, technologists, and access to justice leaders can use this Toolkit to drive court filing modernization in four key areas:

- Filing Technology Infrastructure

- Filing Partner Ecosystems

- Technology Governance

- Forms & Filing Processes

Using This Toolkit

The Filing Fairness Toolkit is designed to guide courts and court stakeholders on their modernization journey to proven, efficient, usable, and sustainable filing systems. This transformation requires leadership, commitment, and change management.

We encourage, and will facilitate, courts working together across jurisdictional lines to implement common, standards-based approaches that will spur innovation and investment in solutions that not only modernize court technology systems but also increase efficiency and improve the ability of all litigants to understand and meaningfully participate in court. Indeed, working together is critical to scalable implementation.

Recommendations center on four important, interlocking categories of change. If your court has already advanced in one or more of these areas, don’t stop reading, but instead continue to sections where improvements can be made. If you are not sure where to start, use the Court Modernization Diagnostic Tool to help you decide which areas to prioritize.

To help make recommendations in this Toolkit more concrete, we specify throughout which are primarily in the purview of:

Judges

Court Administrators

IT Professionals

This may vary by state and jurisdiction. Most importantly, keep in mind that not all technical and logistical challenges should be solved exclusively by IT Professionals, and not all process and rule hurdles will fall exclusively within the purview of judges and Court Administrators.

- Filing Technology Infrastructure

Establish a data-driven and accessible infrastructure through clearly defined connections between filing system components and widely-adopted national standards.

- Filing Partner Ecosystem

Open a marketplace of electronic filing service providers to facilitate a wide range of user-facing tools that align with your court’s mission and goals.

- Technology Governance

Define governance for sustainable vendor relationships and adopt procurement best practices that encourage open marketplaces and avoid vendor lock-in.

- Forms & Filing Processes

Promote easy-to-find-and-use, plain-language document assembly tools with standard form fields, and reduce procedural barriers to enable seamless efiling.

Why Courts Need to Modernize Filing

The technology tools and systems that many state courts use to receive and manage information lags far behind those used throughout the public and private sectors.1 Tax filings, public benefits applications, mortgage applications, and filings in other domains routinely utilize tools that are more effective, less time-intensive, and less costly than current court filing tools.2 In these areas, users can easily access simple, low-cost, plain-language tools to collect required information, generate needed forms or templates, and transfer required data to the agencies or organizations that process that information. Workers can quickly receive information and more efficiently process data, thereby saving time and money.

Outdated and ineffective technology poses particular problems in the millions of court cases filed each year involving self-represented litigants. The National Center for State Courts reports that at least one party is self-represented in three-quarters of all civil cases filed in state court.3

Due, in part, to the high costs of legal assistance and limited supply of legal aid and pro bono services, some unrepresented litigants give up early in the process; they are often unable to find information they need, intimidated by court form complexity and legalese, or deterred by barriers like physical filing and notarization requirements or cumbersome efiling systems.

Other court users complete forms incorrectly, leading to rejection by often-overburdened clerks. Even when litigants properly follow form and filing procedures, the judge may receive legally irrelevant or substantively incomplete information, causing delays that may seriously impact litigants’ lives and create more work for all involved.

Part of the explanation for the current filing technology landscape is the decentralized nature of our civil courts: Forms and filing requirements vary from state to state and sometimes from county to county or courtroom to courtroom. While decentralization can promote local control and customization to local needs, those benefits are often outweighed by substantial costs.

Currently, there is little incentive for decentralized courts to eliminate irrelevant differences between them that increase costs and inhibit modernization. The resulting checkerboard of different filing systems makes it difficult for technology providers to achieve the scale necessary to invest in robust, user-friendly tools.

- This Toolkit helps point the way to sensible coordination, with benefits for all.

The Court Filing Landscape Today

- State courts also vary widely in their technology system infrastructures, efiling vendors they use (if any), the efiling policies they adopt, and how accessible their tools are for both attorneys and the public.

Some courts limit efiling to certain case types and court users, often denying or limiting self-represented litigants’ ability to efile. Many efiling systems also lack connection to document assembly tools that can radically simplify the collection of data and information needed by courts.

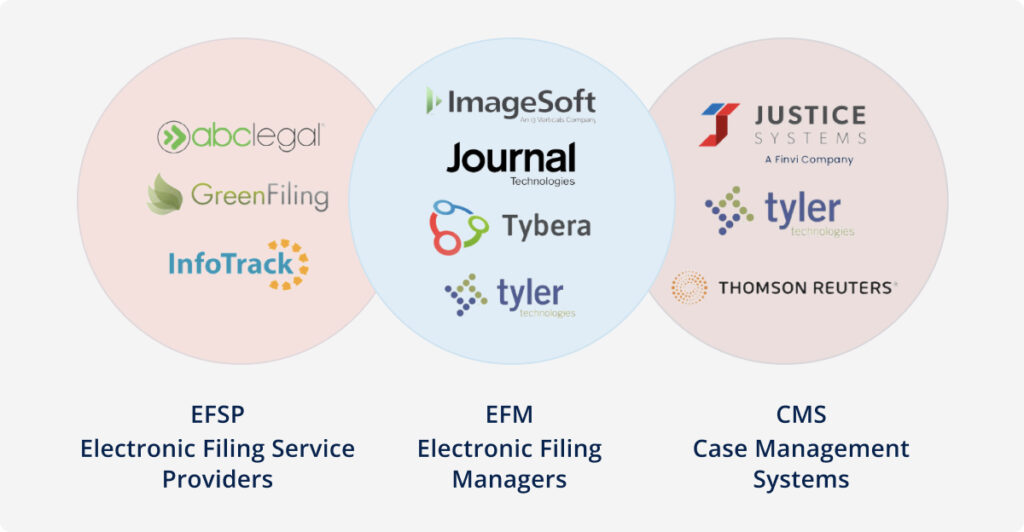

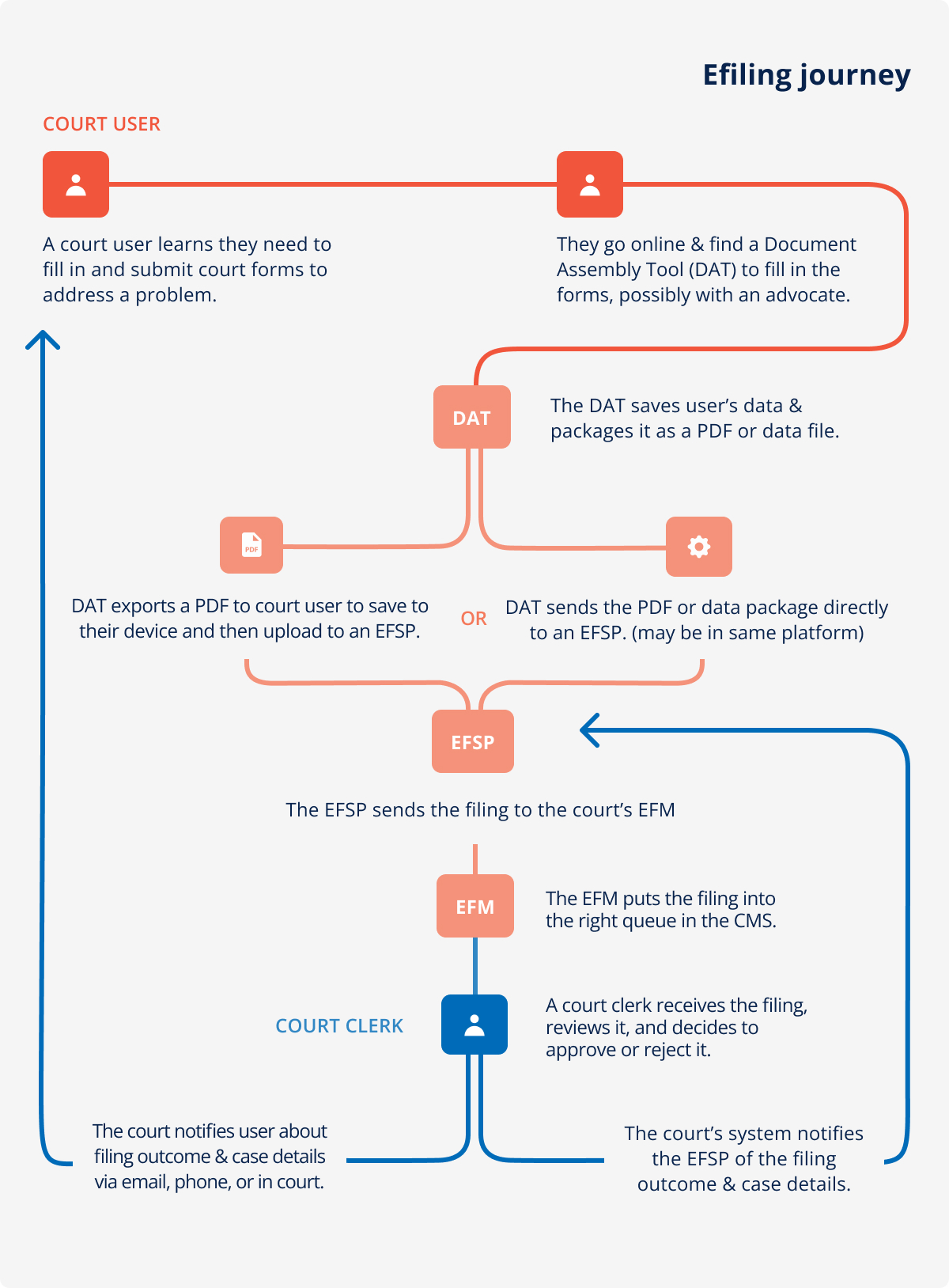

Most state courts partner with one or more third-party vendors for their electronic filing manager (EFM) component, which is the backbone of the efiling system. EFMs accept and route filings to a court’s case management system (CMS). Court users do not interact with either of those systems, but instead they interface with an electronic filing service provider (EFSP) that collects and transfers court documents and data to the EFM. For detailed definitions of these and other court filing terms see Appendix A: Court Filing Glossary.

Often, vendors bundle electronic filing managers and electronic filing service providers together through a single technology solution, but at least nine state courts embrace a multiple-service provider model that allows court users more efiling options and services. In those states, the electronic filing manager vendor allows other third-party vendors to connect with their system.

Several state courts—including those in Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, and Kentucky—have built custom efiling systems. These solutions usually have an electronic filing interface for court users that has been built alongside an internal electronic filing manager (and perhaps a custom case management system). Most states, however, don’t operate this way, and the decision to build or buy an efiling system is complicated and state-specific.

Using third-party vendors is not necessarily better or worse than building a custom filing system, but scaling home-grown systems for wider use is generally not feasible. Vendors can be a great source of expertise and product innovation, and they can eliminate the internal expense of maintaining custom systems. They can also lead to vendor lock-in, which occurs when the cost of switching to a different vendor is so high that you are essentially forced to continue using your current vendor regardless of quality.

- Both custom systems and vendor lock-in can result in a patchwork of incompatible state systems that makes it hard for other vendors (including those that may serve specific case or user types) to develop solutions that can be used across states and jurisdictions.

For this reason, we provide some guidance on procurement policies that can maximize flexibility and choice, minimize costs, and allow for greater innovation and better cross-jurisdictional coordination. Ideally, efiling systems should reduce barriers to filing and make the process of preparing and filing court forms and documents easier and more efficient for both court staff and court users. Depending on how a court’s efiling system operates, users may take different pathways to prepare and file court forms.

- A seamless journey from document preparation to electronic filing, all seemingly within one platform, is more desirable and user-friendly than a process that requires users to navigate multiple disparate technology platforms.

A Path to Practical, Impactful Filing Modernization

The underlying technology driving modernization in other sectors is already tried and tested such that no “invention” is needed to significantly improve court filing operations. In particular, simplified efiling user interfaces and readily available document assembly tools that offer plain language questions to complete forms will give courts the information they need in the form they want. Robust relationships between courts and an ecosystem of technology partners linked by common standards can open the door for innovative solutions.

The entire court ecosystem gains from modernization. Clerks won’t need to manually copy data from physical forms into their court’s case management system when all litigants can efile. They won’t need to reject as many incomplete filings when the proper information is entered through a certified document assembly tool that ensures complete and accurate forms. Court administrators won’t need to coordinate time-and-resource-intensive system integrations when they want to make small changes to their technology infrastructures. Lawyers will save time by using the same efficient document assembly and efiling tools that self-represented litigants can also utilize, particularly for less-familiar practice areas. Understaffed legal aid organizations will be able to leverage these tools to prioritize work they are uniquely qualified to do instead of filling out forms for high volume case loads. And judges will receive more relevant and complete legal information.

Litigants who provide necessary information to courts via plain language document assembly tools, and then file those forms online, are spared the logistical burdens of determining what forms to prepare, locating those forms, entering duplicative information, and having to physically visit a courthouse. Modern document assembly and efiling tools can generate forms that promote completeness and avoid common procedural pitfalls. These tools can also help litigants understand what information is being requested and their next steps, thereby improving substantive outcomes, perceived fairness, and public trust in courts.

Many of the recommendations within this Toolkit have already been deployed in at least one state court. Some have resulted in significant cost savings. For example, one Florida study found that the efiling of more than 2 million documents a year saved nearly $1 million. Courts that have already implemented filing modernization projects serve as replicable models for other courts. They may also offer opportunities to partner with experienced experts, including court administrators, judges, and technology providers who can help you understand where your court stands and recommend where it should go.

Quite the opposite: Much of setting up a future-proof, modernized court filing system is about good contracting and organizational design that makes clear the values and services that courts expect from their vendors. These are changes that judges and court administrators can—and should—be involved in making. This Toolkit both proposes specific steps and recommends who should be responsible for implementing them.

Benefits of Modernization

- Court Staff & Clerks

- Judges

- Lawyers

- Legal Aid Organizations

- The Public

Maturity Models

The Filing Fairness Project team developed Maturity Models for the four categories of change addressed in this Toolkit. Each model illustrates how modernization efforts advance a court’s filing system and user experiences. This chart summarizes the Maturity Models for each category and lays out moderate, good, better, and advanced stages of development.

These models are discussed further in each category of change, with examples of courts across the country that have already achieved higher levels of maturity. You may notice that your court is further along the scale in some areas than it is in others—but be assured that wide-reaching progress is doable!

| Category | MODERATE | GOOD | BETTER | ADVANCED |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filing Technology Infrastructure | Court offers basic efiling, but no open interface to connect components.10 | Court provides a standards-based efiling system with a basic open interface. | Court provides a modern standards-based efiling system with an easy-to-use open interface. | Court provides a seamless, connected efiling system with an easy-to-use open interface. |

| Filing Partner Ecosystem | Efiling system comprises a single vendor or a custom built efiling system. | There are a small number of established vendors in the filing partner ecosystem. | A broader partner ecosystem exists, with some alignment to the court’s access to justice goals. | A diverse ecosystem facilitates access for providers and aligns with the court’s access to justice goals. |

| Technology Governance | Limited or no efiling vendor certification process. | Basic efiling vendor certification process with integration requirements. | Efiling vendor certification process promotes partner vendors and has low-cost integration requirements. | Robust efiling vendor certification process incorporates future-looking integration requirements. |

| Forms & Filing Processes | Court offers blank PDF forms with limited guidance; there are efiling barriers and no available support. | Basic document assembly tools exist along with reduced efiling barriers and some in-person support. | Court provides user-friendly document assembly tools, there are minimal efiling barriers, and in-person or virtual support exists. | Court provides easy-to-find and effective document assembly tools with no efiling barriers and robust in-person and virtual support. |

Court Modernization Diagnostic Tool

Use this diagnostic tool to help determine where to focus your filing system modernization efforts.

- More “YES” answers mean that your court is further along in modernizing that category. Focus more on recommendations in this Toolkit for categories where you’ve answered “NO.”

| Does your court offer efiling in all counties and courts? | ||

| Is efiling available for all civil case types? | ||

| Are all litigants allowed and able to use the efiling system? | ||

| Does your court use the Electronic Court Filing Standard (ECF 5 or at least ECF 4) to allow easy integration of new technology vendors with your efiling system? | ||

| Does your electronic filing manager component have an open interface (an “API”) that clearly defines how third-party service providers can connect to it? |

| Does your court offer a diverse set of efiling tools for various user & case types? | ||

| Does your court require vendors to demonstrate a commitment to your access to justice goals before admitting them to your partner ecosystem? |

| Does your court have a defined certification process for vendors to become an efiling technology provider? | ||

| Is your efiling manager vendor motivated to add new efiling service providers? |

| Does your court provide a form for most major case types? | ||

| Does your court offer document assembly tools? | ||

| Do guided interviews use plain language and user-tested design elements? | ||

| Are document assembly tools easily discoverable by court users? | ||

| Are document assembly tools certified to efile court documents? | ||

| Does your court accept electronic signatures, notarization, and payments? | ||

| Does your court have a transparent, standard fee waiver process? | ||

| Does your court provide support to court users for forms, filing, and court processes? |

1 This document is primarily concerned with civil court filings; however, many courts use the same filing system for civil and criminal cases. The recommendations within may accordingly benefit both case types.

2 See, e.g., Comm’n on the Future of Legal Servs., Am. Bar Ass’n, A Report on the Future of Legal Services in the United States 18, 27 (2016), https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/images/abanews/2016FLSReport_FNL_WEB.pdf (discussing cost reduction from document automation and document review tools); Jaqueline Kauff, Emily Sama-Miller & Elizabeth Makowsky, Mathematica Pol’y Rev., Promoting Public Benefits Access Through Web-Based Tools and Outreach: A National Scan of Efforts (2011), https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//113586/BAS2011Vol1.pdf (documenting the extensive proliferation of web tools for applying for public benefits, even back in 2011).

3 Paula Hannaford-Agor, Scott Graves & Shelley Spacek Miller, Nat’l Ctr. for State Cts., The Landscape of Civil Litigation in State Courts, at iv (2015), https://www.ncsc.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/13376/civiljusticereport-2015.pdf.

4 Nat’l Ctr. for State Cts., Self-Represented Efiling: Surveying the Accessible Implementations 9-11 (2022), https://www.ncsc.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/76432/SRL-efiling-1.pdf

5 The Filing Fairness Project does not endorse any vendors or products. We have shared different vendors utilized by state courts to demonstrate the variety of available options.

6How Courts Embraced Technology, Met the Pandemic Challenge, and Revolutionized Their Operations, PEW CHARITABLE TRUSTS (Dec. 1, 2021), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2021/12/how-courts-embraced-technology-met-the-pandemic-challenge-and-revolutionized-their-operations; see also Abhijeet Chavan, Admin. Off. of Ill. Cts., Improving the E-Filing Experience for Self-Represented Litigants in Illinois 6-7 (2022), https://ilcourtsaudio.blob.core.windows.net/antilles-resources/resources/76c2460f-ddce-4e8a-9c9e-53535e71d0a4/Improving%20the%20E-Filing%20Experience%20for%20Self-Represented%20Litigants%20in%20Illinois.pdf.

7See generally Chavan, supra note 4 (noting the importance of step-by-step guidance given the complexity of the Illinois efiling process).

8See Chavan, supra note 4, at 26; Nat’l Ctr. for State Cts., Self-Represented Efiling: Surveying the Accessible Implementations 4, 8 (2022), https://www.ncsc.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/76432/SRL-efiling.pdf (noting that “SRL filers often benefit from guided online questions” and that “technology barriers can feed a perception that one’s participation in the courts doesn’t matter”); see also Margaret Hagan, Community Testing 4 Innovations for Traffic Court Justice, MEDIUM (Dec. 15, 2017), https://medium.com/legal-design-and-innovation/community-testing-4-innovations-for-traffic-court-justice-df439cb7bcd9 (discussing user-tested preferences for and belief in automated tools in traffic court).

9Jenni Bergal, Courts Plunge Into the Digital Age, PEW CHARITABLE TRUSTS: STATELINE (Dec. 8, 2014, 12:00 AM), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2014/12/8/courts-plunge-into-the-digital-age; Calculating an E-Court Return on Investment (ROI), Nat’l Ctr. for State Cts (Feb. 16, 2012) https://courttechbulletin.blogspot.com/2012/02/calculating-e-court-return-on.html.

6 How Courts Embraced Technology, Met the Pandemic Challenge, and Revolutionized Their Operations, Pew Charitable Trusts (Dec. 1, 2021), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2021/12/how-courts-embraced-technology-met-the-pandemic-challenge-and-revolutionized-their-operations; see also Abhijeet Chavan, Admin. Off. of Ill. Cts., Improving the E-Filing Experience for Self-Represented Litigants in Illinois 6-7 (2022), https://ilcourtsaudio.blob.core.windows.net/antilles-resources/resources/76c2460f-ddce-4e8a-9c9e-53535e71d0a4/Improving%20the%20E-Filing%20Experience%20for%20Self-Represented%20Litigants%20in%20Illinois.pdf.

7 See generally Chavan, supra note 4 (noting the importance of step-by-step guidance given the complexity of the Illinois efiling process).

8 See Chavan, supra note 4, at 26; Nat’l Ctr. for State Cts., Self-Represented Efiling: Surveying the Accessible Implementations 4, 8 (2022), https://www.ncsc.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/76432/SRL-efiling.pdf (noting that “SRL filers often benefit from guided online questions” and that “technology barriers can feed a perception that one’s participation in the courts doesn’t matter”); see also Margaret Hagan, Community Testing 4 Innovations for Traffic Court Justice, MEDIUM (Dec. 15, 2017), https://medium.com/legal-design-and-innovation/community-testing-4-innovations-for-traffic-court-justice-df439cb7bcd9 (discussing user-tested preferences for and belief in automated tools in traffic court).

9 Jenni Bergal, Courts Plunge Into the New Age, PEW CHARITABLE TRUSTS: STATELINE (Dec. 8, 2014, 12:00 AM), https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2014/12/8/courts-plunge-into-the-digital-age; Calculating an E-Court Return on Investment (ROI), Nat’l Ctr. for State Cts (Feb. 16, 2012) https://courttechbulletin.blogspot.com/2012/02/calculating-e-court-return-on.html.

10 Open interfaces for filing system component connections are critically important—they are why we can read our favorite websites regardless of whether we are on a mobile device or a laptop, or using Apple products or Android-based products. An Application Programming Interface or ”API” refers to open interfaces, and it will be referenced throughout this Toolkit.

Open Appendix Menu

Court filing glossary

Sample checklist for vendor alignment with access to justice goals

Sample usability rubric for forms and document assembly tools

Court filing glossary

Sample checklist for vendor alignment with access to justice goals

Sample usability rubric for forms and document assembly tools